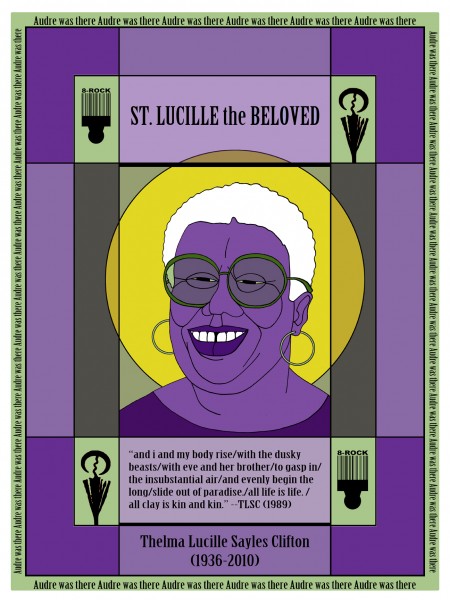

Lucille Clifton was one of the most highly regarded poets of the last half-century. Her career spanned most of the last fifty years, with her work only growing stronger, more imaginative, and more profound over time.

When Lucille Clifton died in 2010, I was stunned, not because I was unaware of her health struggles over the years, but because it never occurred to me that I would never have a chance to meet her. Her work was such a significant part of my life for so long that she felt like a friend.

I first encountered Lucille Clifton’s work back in the 1970s, when I was in elementary school. When I was a kid, my mom took me to the library almost every week, and one day she brought home one of the books from Clifton’s Everett Anderson series. These wonderful picture books revolved around the life of young Black boy, and in the 1970s, books depicting Black children were few and far between. We read all of the Everett Anderson books, or at least all of the ones that were published while I was still young enough to appreciate being read too. That, however, was the extent of my knowledge of Clifton’s work until I was in college.

Imagine my surprise when, in my sophomore year, the poet C.D. Wright introduced our creative writing class to Clifton’s poetry. There was little of the children’s-book-writing Lucille Clifton in the work of the poet Lucille Clifton. Her poetry was edgy, audacious, unflinching, and adult. And when it came to her numerous poems about religion and myth, her work was both sacred and impious, often simultaneously.

Clifton also wrote extensively about motherhood, friendship, marriage, and ancestry; and all of her poems vibrated with an undercurrent of love and wonder–for the women figures so often overlooked in the ancient texts of world religions, for her life’s journey as mother-wife-daughter-sistafriend, for her ancestors both named and unnamed, for the curiosities and wonders that the world has to offer, and for Black people.

I was thrilled to discover this additional dimension of one of my favorite childhood writers, and Lucille Clifton and her poems became regular reading for me during the remainder of my undergraduate years.

Clifton became an even more central part of my life in graduate school. She figured prominently in one chapter of my dissertation (and later in my book, Inventing Black Women); and one of her poems became my daily inspiration during that hectic last year of my graduate program. I was teaching in the Women’s Studies program at the university, I was applying for academic jobs, and I was finishing my dissertation. It was one of the most stressful periods I’d ever experienced, and I needed all the support I could find. Some time during the fall of that year, I posted one of Clifton’s poems on the wall above my computer:

hag riding

why

is what i ask myself

maybe it is the afrikan in me

still trying to get home

after all these years

but when I wake to the heat of morning

galloping down the highway of my life

something hopeful rises in me

rises and runs me out into the road

and i lob my fierce thigh high

over the rump of the day and honey

i ride i ride.

During that make-or-break year in my academic life, this poem was a daily reminder of my own power and persistence.

Throughout the 19 years since I completed my Ph.D., Lucille Clifton has been a staple in my teaching. I have taught her poems in classes both on and off the campuses where I’ve worked, at writing workshops, and even at churches. And when I was called to speak at my grandmother’s funeral service, Lucille Clifton’s “won’t you celebrate with me” provided me with the right words.

In creating this drawing of Clifton, I encountered her poems anew, through the eyes of other people who love her work. Sometimes, when you are really, truly touched by a book or a body of work, it can feel like it belongs only to you. But, browsing through the many blogs and websites on which Clifton’s most loyal readers have paid homage to the poet and her words, I have come to enjoy the other side of truly appreciating a writer–the community of her fans.

***

For a literary biography of the poet, with detailed information about her faculty appointments, awards, and award nominations, along with a full bibliography of her publications, check out the Lucille Clifton page on The Poetry Foundation website.

Ajuan Mance