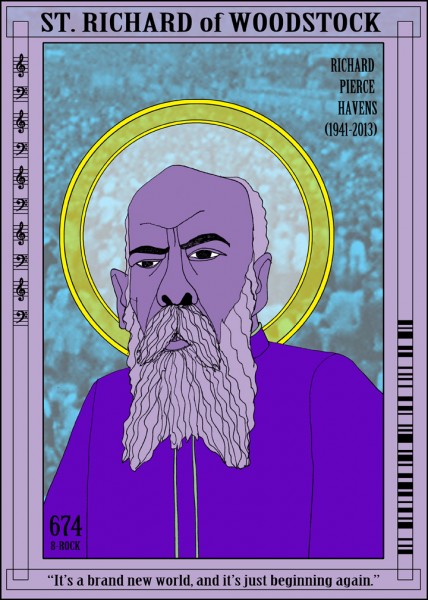

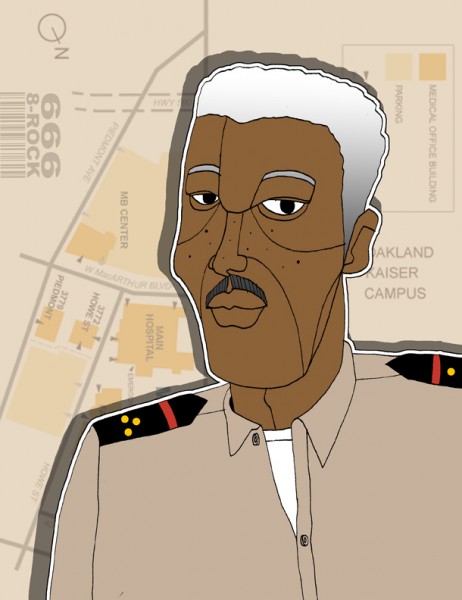

From the Rolling Stone Magazine obituary by David Browne:

The oldest of nine children, Havens grew up in Brooklyn’s poor Bedford-Stuyvesant, the son of a factory worker who played piano; as a teenager, Havens formed a gospel group in high school. Although at one time he said he hoped to be a surgeon, he left home at 17 and landed in Greenwich Village. When he wasn’t painting portraits of tourists to make money, Havens was playing the folk clubs there. Among those who noticed him was Dylan: “One singer I crossed paths with a lot, Richie Havens, always had a nice-looking girl with him who passed the hat and I noticed that he always did well,” Dylan wrote in his memoir Chronicles: Volume One.

After recording two albums for a small label, Havens hooked up with Dylan’s manager, Albert Grossman. With that, Havens’ visibility jumped up a new notches. In 1966, Havens was signed to Verve/Folkways, who released his classic Mixed Bag that year. Havens already had a growing audience thanks to albums like 1968’s ambitious blues-folk-psychedelic double LP Richard P. Havens, 1983, when he signed up for Woodstock. Recalling his trip into the grounds by helicopter, he later said, “It was awesome, like double Times Square on New Year’s Eve in perfect daylight with no walls or buildings to hold people in place.”

Havens wasn’t supposed to be the first act to open the festival; that slot originally was intended for the band Sweetwater, but that band wound up being stuck in traffic. Backstage, co-organizer Michael Lang approached Havens and practically begged him to go on instead. “It had to be Richie – I knew he could handle it,” Lang later wrote.

After performing a half-dozen songs, Havens ran out of material – until, he later said, he remembered “that word I kept hearing while I looked over the crowd in my first moments onstage. The word was: freedom.” Havens began chanting that word over and over, backed by his second guitarist and conga player, and eventually segued into the gospel song “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child,” which he had heard in church as a child. The combined, surging medley wasn’t just a crowd-pleaser; it later became a highlight of the Woodstock movie, which also immortalized Havens’ orange dashiki. (What many didn’t know at the time was that Havens wore dentures, which also gave his singing voice a unique tone.) “My fondest memory was realizing that I was seeing something I never thought I’d ever see in my lifetime – an assemblage of such numbers of people who had the same spirit and consciousness,” he later recalled of Woodstock to Rolling Stone.

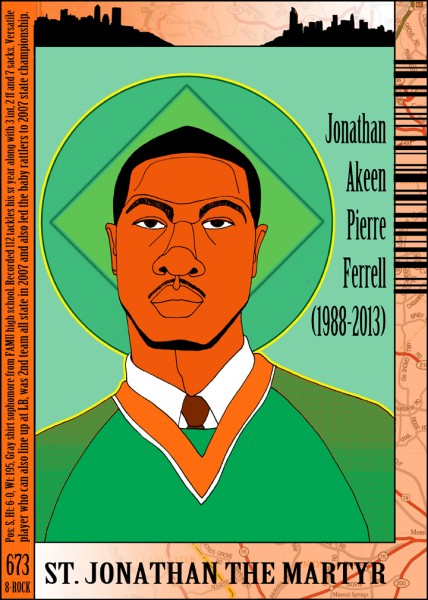

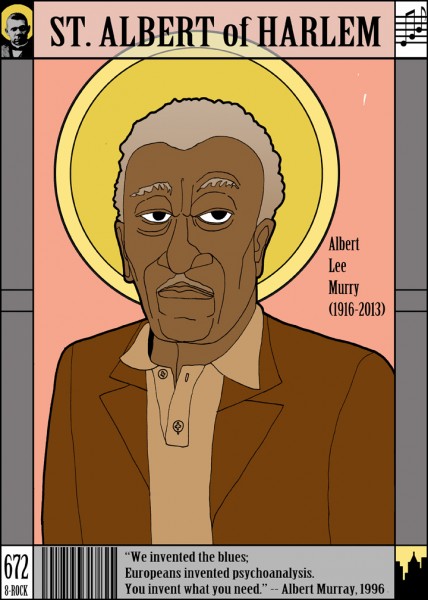

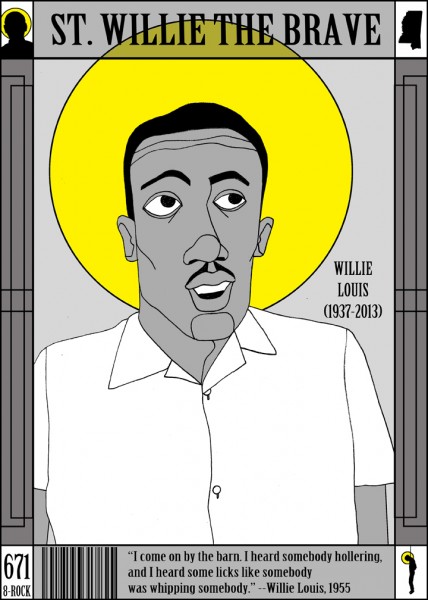

Ajuan Mance