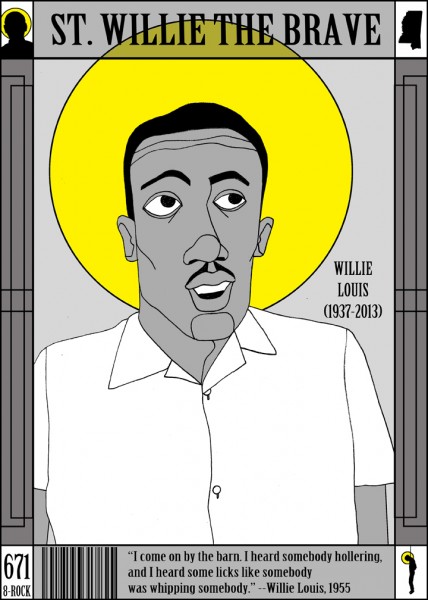

The truck was going “real fast,” Willie Reed testified, as it came down the main road near Drew, Miss., on an August morning.

A green and white 1955 Chevrolet — that year’s model — it passed Mr. Reed as he was walking to the store, turned into a nearby plantation and parked in front of a barn.

In the cab, Mr. Reed said, were four white men. In the rear were three black men, plus a fourth — a black youth hunkered down in the very back of the truck.

Soon afterward, Mr. Reed said, he heard “somebody hollering” and “some licks like somebody was whipping somebody” coming from the barn.

The youth in the truck was named Emmett Till, and he would not be seen alive again.

The next month, the 18-year-old Mr. Reed, after braving intimidation from one of the suspects and walking through the thicket of Klansmen massed outside the courthouse, testified in open court to what he had seen and heard.

The son of a family of black sharecroppers, Mr. Reed was spirited out of Mississippi immediately after the trial. He changed his name to Willie Louis and lived discreetly in Chicago, where he worked as a hospital orderly.

Mr. Louis, one of the last living witnesses for the prosecution in the Till case, died on July 18 in Oak Lawn, Ill., a Chicago suburb. He was 76.

Till, had he lived, would have been 72 this Thursday.

The murder of Till, a 14-year-old Chicagoan visiting family in Mississippi, and the ensuing trial are watershed moments in the civil rights movement, galvanizing public attention on the deep perils of being black in the Jim Crow South.

Though the two white men tried for the murder were acquitted, the testimony of Mr. Reed was considered so powerful that it made him a hero of the movement — albeit a quiet, accidental and long unsung one, who spoke of the case only rarely and with obvious pain.

“Willie Reed stood up, and with incredible bravery pointed out the people who had taken and murdered Emmett Till,” the filmmaker Stanley Nelson, who interviewed Mr. Louis for his 2003 PBS documentary, “The Murder of Emmett Till,” said Wednesday. “He was from Mississippi, and somewhere in his heart of hearts he had to know that these people would not be convicted. But he did what he had to do.”

For decades, Mr. Louis told no one of his involvement in the case. Even his wife, Juliet, whom he married in 1976, did not learn of it until eight years later, when a relative told her.

He began speaking about it publicly only in recent years, with the release of Mr. Nelson’s film and another documentary, “The Untold Story of Emmett Louis Till” (2005), directed by Keith Beauchamp.

“I couldn’t have walked away from that,” Mr. Louis told the CBS News program “60 Minutes” in 2004, speaking of his decision to testify. “Emmett was 14, probably had never been to Mississippi in his life, and he come to visit his grandfather and they killed him. I mean, that’s not right.”

Mr. Louis was born in Greenwood, Miss., in 1937 and as a youth lived with his grandfather in Drew. He worked in the fields picking cotton and received little formal education: though he was 18 at the time of the trial, he was only in the ninth grade.

On Aug. 21, 1955, Emmett Till arrived in Money, Miss., about 30 miles from Drew, to stay at the home of a great-uncle, Moses Wright. On Aug. 24, Till visited Bryant’s Grocery and Meat Market, a store in Money owned by a white couple, Roy and Carolyn Bryant.

Inside the store, Mrs. Bryant later testified, Till grabbed her hand and made a sexual suggestion. Leaving the store, according to some accounts, he let out a wolf whistle.

Early in the morning on Aug. 28, Mr. Bryant and his half-brother J. W. Milam abducted Till from his uncle’s home. His body, brutally beaten, shot in the head and weighed down with a cotton-gin fan laced round his neck with barbed wire, was found in the Tallahatchie River three days later.