It’s taken me 400 drawings to finally begin to figure out exactly what I’m doing in this project. In some ways, what I am doing is pretty obvious: I am creating an online sketchbook of the Black men and boys I encounter in my everyday life. There are other dimensions to this project, though, one of which I have only recently begun to consider in earnest.

My goal in this project has been to draw men (and some boys) of African descent just as they are, without projecting my own interests and needs onto the subjects I depict. I’ve posted a little about this before. What I didn’t mention in my previous post on this topic is that part of my inspiration was an issue of Essence Magazine. Are you familiar with Essence? It’s subtitle is The Magazine for Today’s Black Woman, and that pretty much sums up its purpose and its editorial content. I should mention that I love Essence Magazine. Although I no longer read it on a regular basis, I believe it has done a good job of privileging and advancing the interests of U.S. women of African descent. I don’t, however, believe that Essence has been quite as successful in its depictions of Black men.

Although the stereotype (left over from residual anger about Black women novelists’ treatment of relationship violence against Black wives and girls) is that Black women writers tend to portray Black men in a derogatory manner, the writers in Essence Magazine do exactly the opposite. In its annual “Men We Love” issue, Essence offers up a view of African American men and masculinity that could only be described as fantastical and laudatory. This issue offers little in the way of any critique of Black men, which is fine; but it does so, in part, by portraying such a narrow swath of Black manhood that all but the wealthiest, most conventionally successful men are completely overlooked. In portraying the “Men We Love,” Essence offers up a revisionist portrait of Black manhood, not as it actually exists in the world but, rather, as the (mostly) female editorial board would like it to be.

There is, mind you, some value in this approach. After all, white women have plenty of space in plenty of periodicals to fantasize about those qualities that they idealize in men and about those male actors and singers and athletes who embody those qualities. I see no problem with Essence creating a space in which Black women can do the same. This issue did, however, highlight for me the degree to which even Black-owned and Black-edited publications contribute to a media culture that tends to see people of African descent–and men of African descent, in particular–not as who they are, but as who a given newspaper/magazine/film/television audience wants or needs them to be … which brings me to what I am doing in this project (and in this drawing).

I have, during my first 400 drawings, largely succeeded in drawing the Black men whose portraits are featured pretty much as I encountered them. I draw live, from memory, or from photos taken on my smartphone; and my drawings resemble not my fantasy of the men I have seen, but the men themselves. My drawings, however, fall far short of representing the full range of Black men that I see. Despite the quantity of drawings I have created, they do not in any way offer a representative sampling of the Black men I have seen, or even of the men I see most often. Rather, they depict the men I notice, and what I notice has an awful lot to do with what I find interesting, compelling, comfortable, and (sometimes) even beautiful.

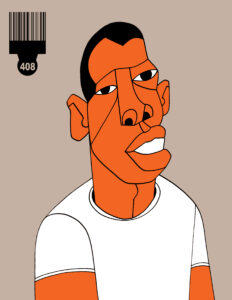

The drawing at the top of this page pretty much exemplifies my biases. You see, from where I live in Oakland, I have to drive down High Street to get almost anywhere I want to go; and I see a lot of Black men as I drive down this street every day. Yet, I rarely draw any of the men and boys I see there. Consider this: A lot of the youth I see on this street are still wearing the outfit that was ubiquitous when I began this project. Despite the fact that the skinny jean and the brightly colored hoodie and sneakers have made significant inroads into Black teen style, a lot of the young High Street brothers are still rocking the super baggy, over-sized jeans, the big white t-shirts, and black hoodies. Despite the fact that I see a lot of young Black men dressed in this way almost every day, very few of the subjects of my drawings are wearing these clothes. Even though my drawings depict men who I see, I am realizing that I only see Black men selectively. I look at lots of people, but in terms of really truly seeing Black men in the way that I have to in order to draw them later on, I seem too look past the young brothers on the corner in the baggy pants. I don’t really see them.

So this is the challenge for my final 600 drawings: I need to sample more widely and represent not just the truth of the men who I notice. Rather, I need to reexamine and re-calibrate who and how I notice Black men and boys. The 1001 Black Men online sketchbook is my project in that I have created these drawings and they are mine; but it is also a community portrait of a group of whom I am not a part, and that fact brings with it a level of responsibility to the Black men and boys who are my subjects. I have to be mindful of that, to think about what that means, and to re-imagine how my art can reflect not only those truths about the breadth of Black manhood and masculinity (and femininity) that are comfortable and familiar, but also those truths that are somewhat less familiar and that challenge my own experiences and sensibilities.

Ajuan Mance